Today we’d like to introduce you to Lydia Greene.

Hi Lydia, thanks for sharing your story with us. To start, maybe you can tell our readers some of your backstory.

Growing up in the concrete jungle of New York City, I had no idea I would become a lemur scientist. I had no idea what lemurs were and had little connection to either the scientific or natural world. Instead, I trained hard to become a professional ballerina. But after my attempt at a dance career was cut short by a body that wasn’t made to industry standards, I moved back home with my folks, worked in service, and hatched a plan to try my hand at college.

Within my first weeks at Duke University, I found lemurs. I needed a work-study job and the Duke Lemur Center needed educational docents. I soon learned that the Duke Lemur Center maintains the largest and most diverse collection of lemurs outside of their native Madagascar with a trifocal mission of non-harmful lemur research, conservation, and public education. I fell immediately in passion with the animals and the mission. I concurrently began taking classes in Evolutionary Anthropology and volunteered in a lab studying female dominance and communication (yep, in lemur societies females are generally dominant over males). Within a few short years, I was leading my own project on scent marking in sifakas.

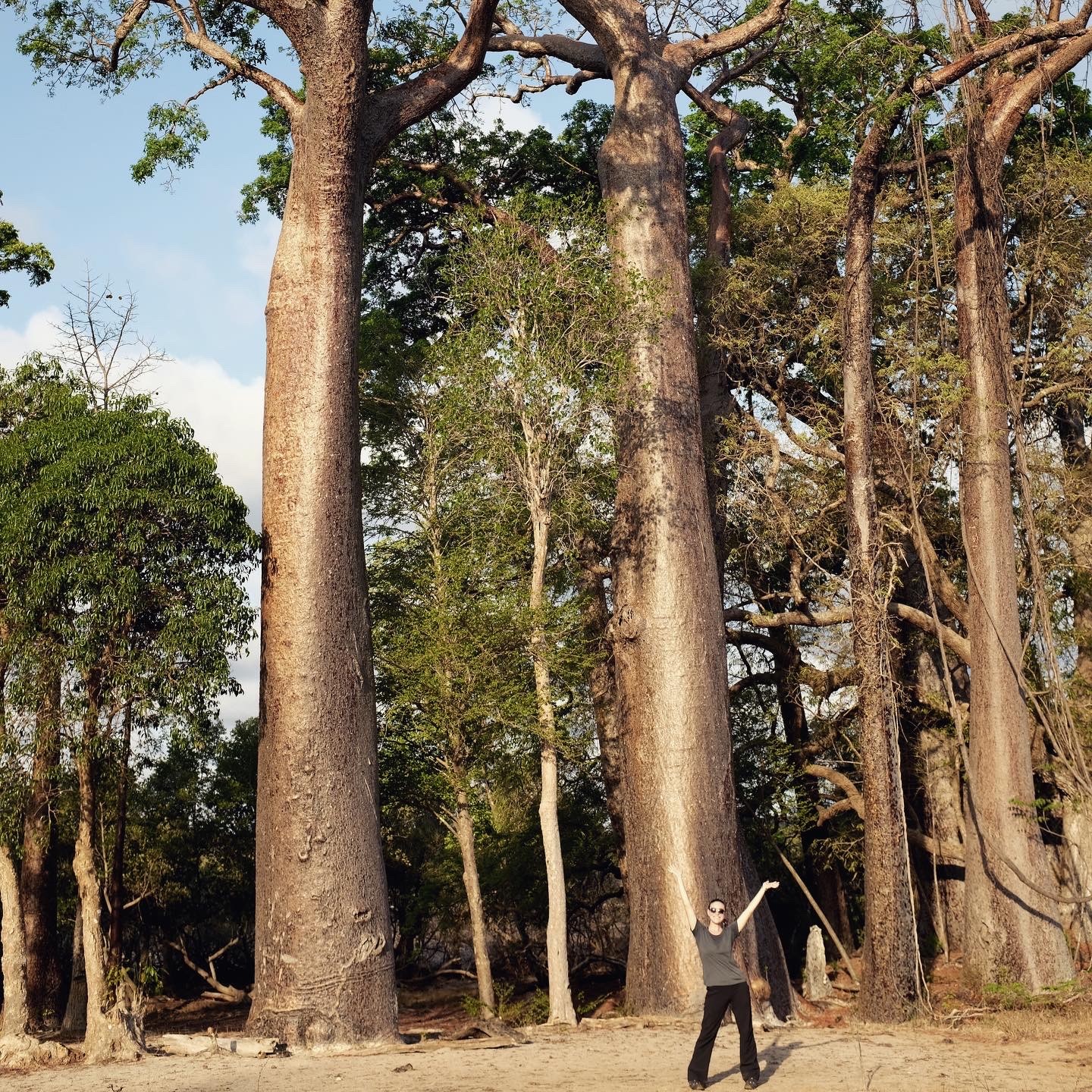

Fast forward and I earned my PhD from Duke’s Ecology program in 2019. For my dissertation, I researched the links between the gut microbiome and nutritional ecology in leaf-eating lemurs. Along the way, I came out as gay to myself and the world and married another lemur scientist (hi Marina!) and began working in Madagascar to deepen my understanding of wild lemurs while building a network of collaborators that share my interests and passions.

Today, I’m a Research Scientist at the Duke Lemur Center where I continue to study nutritional ecology, health, and the gut microbiome with applications towards lemur husbandry and conservation. I guess it’s been a rather unusual journey from Manhattan to Madagascar, but I’d do it all over again.

We all face challenges, but looking back would you describe it as a relatively smooth road?

I’m very lucky in that I’ve never struggled to have my basic needs met. Against that backdrop of security, there have been periods along my journey tainted by anxiety, frustration, and fear.

The biggest period of uncertainty for me came after I left the ballet world. I felt lost and ashamed. My body had failed me and my mind couldn’t yet see a path forward filled with purpose or passion. While the body issues remain to this day, my fear about my future mostly dissipated when I became passionate about lemurs and science in college.

Now as a professional scientist, I struggle most with imposter syndrome. It comes with these nagging feelings of not being good enough, of everyone realizing I’m a fraud, and the lingering fear of disappointing people I love and respect. I’m working on paying less and less attention to these feelings as I get older and older, but it’s a marathon and not a sprint.

Outside of these concerns, I think most folks connected to the conservation world struggle with the emotional toll taken by the environmental and extinction crises facing the ecosystems and species we love.

Can you tell our readers more about what you do and what you think sets you apart from others?

I’m a research scientist at the Duke Lemur Center, which means I wear many hats. On any given day, you might find me observing lemurs in the forest, analyzing samples in the lab or data on my computer, writing up the results of a study for publication or writing grants to fund future projects. You might find me mentoring students or being mentored by colleagues. I might be in team meetings brainstorming new ideas (one of my favorite things) or giving presentations on ongoing studies. You can also find me engaging in science communication on my professional Instagram (@lemurscientist) or by collaborating with our Education Department. There’s a huge range of tasks that make up a science career: I love most that I get to work with collaborative teams and that every day is different.

Ultimately all these tasks revolve around studying lemurs, the incredible primates that live only on the island of Madagascar. Lemurs are fascinating for many reasons, but I’m particularly curious about the diverse feeding and metabolic strategies that allow different species to survive and thrive in strongly seasonal and challenging environments and how those strategies came to be in the first place.

My current work is focused on understanding health and nutrition in lemurs, and I specialize in the Coquerel’s sifakas (who are obviously the best type of lemur). I’m fascinated by how these animals mediate their own nutrition and health while eating flexible diets of leaves, fruits, flowers, seeds, bark, and even soil that vary depending on what’s available in the forest. At Duke, our lemurs free-range in expansive forest enclosures from spring through fall, where they forage on a rich array of endemic plants.

I spend many days in the woods documenting what our sifakas choose to eat across seasons. I collect samples of those food items for nutritional analysis and I collect fecal samples to profile the lemurs’ gut microbiomes and metabolites. In collaboration with our veterinary department, I collect blood samples to profile circulating hormones, amino acids, fatty acids, sugars, white-blood cells, minerals, and vitamins, among other markers of health, nutrition, and stress. All these bits of information combined can help us paint a picture of how lemurs cope with seasonality and how they adapt to environmental change. Moreover, these bits of information can help us better provide for the lemurs under our care. Research on lemur nutrition, gut microbiomes, and health can inform the diets we offer the lemurs and can help us maintain them under the most naturalized conditions possible.

It’s hard to come up with the things I’m most proud of. I’m certainly proud of my scientific achievements and the inspiring students I’ve mentored. But I would say I’m more excited about what our team could do in the future rather than what we’ve done in the past. I’m excited by the prospect of continuing to work with collaborative teams of western and Malagasy experts comprising scientists, veterinarians, and husbandry professionals to address ongoing and emerging concerns in lemur welfare and conservation. And I’m excited to create new opportunities for students of all backgrounds to engage in lemur science.

It’s also hard to come up with the things that set me apart from others because I feel most comfortable and successful when working in teams, where every member brings to the table a unique set of experiences and perspectives. I asked my wife to help me answer this question and she said it’s my combined commitment to scientific rigor and science communication.

So, before we go, how can our readers or others connect or collaborate with you? How can they support you?

You can contact me on Instagram (@lemurscientist) or by email (lydia.greene@duke.edu). I’m quite good about responding to DMs and emails!

Typically, students reach out to me to ask how they can get involved in lemur science projects. As much as possible, I try to tailor research opportunities to the interests and skills of each student. I also co-mentor students and early-career researchers through a variety of initiatives in the US and international collaborators in the UK and Madagascar.

You can also learn more about the Duke Lemur Center, our animals, our mission, and our tour program by visiting lemur.duke.edu.

Contact Info:

- Email: lydia.greene@duke.edu

- Website: lemur.duke.edu

- Instagram: lemurscientist